How to Survive Kumagaya Summer

Top Image: creampastaさん on PhotoAC

あついぞ!熊谷 or “Very Hot! Kumagaya!” is the catchphrase of the city in which I live. Kumagaya in Saitama Prefecture is known for being the hottest city in Japan. Just to give you an idea, in August 2007 Kumagaya broke the 74-year record for the highest temperature recorded in Japan, 40.9C (105.6F).

In July 2018 it broke this record again with a temperature of 41.1C (106.0F). Needless to say it gets very hot here in summer, so hot that heatstroke is a very big problem here. I’ve lived in Kumagaya for the past seven years so I’ve managed to pick up a few things on how to survive the blistering heat! With another summer fast approaching us, let’s dive right in!

Cool Towels

If you go anywhere in Japan in Summer you will see people with towels around their necks. Not only are they great for wiping the sweat from your face and neck, but recently you can get towels that when wet are very very cool! You can get these towels from a lot of different store, even Daiso has them!

The ones that I am currently using are fruit themed and I got them from my local Threppy (300 yen shop)! All you do to use them is wet them in some water, wring out the excess (because if you don’t your shirt will get very very wet) and then wrap it around your neck and embrace the cool cool escape!

Personal Fans

Photo Credit: ユミミンさん on PhotoAC

Fans are amazing in summer, but did you know you can get personal ones? And no I’m not talking about a desk fan! I’m talking about a fan that you can hold in your hand! Or even put around your neck to wear on the go!

I first saw these about two or three years ago; back when summer festivals were still a thing! I was very skeptical at first but boy are these things amazing! I mean I’m not going to lie, they look very silly, but when you have your own personal cool bubble… who cares?

Throat Lollies

Heatstroke. As I mentioned above, heatstroke is a very big problem in summer. If you’re unaware, heatstroke is caused by your body overheating. A big cause for heatstroke is becoming dehydrated by not drinking enough water to replenish fluids lost through sweating. More on drinks below, but another way you can help your body is to suck on some throat lollies.

And no I’m not talking your sore throat lollies. I’m talking, lemon and plum (ume). You can get these from your local supermarket, pharmacy or even the conbini! They are very cheap and now that we have to wear masks, no one at your work will even notice! My personal favourite is the 塩分チャージタブレット sports drink flavour. They melt very quickly though, so I tend to have a lot of these in a day.

Sports Drinks

Photo Credit: akizouさん on PhotoAC

Heatstroke. We meet again, but not this time! Let’s face it, sometimes water just isn’t enough! If you’re like me and you sweat a lot, but even though you drink a ton of water you still come home with a headache, get some sports drinks. Aquarius, Pocari Sweat to name a few are amazing!

You can buy a box full of premade bottles, or you can just get the powder and make your own like I do! Looking on Amazon Japan, you can get a box of Pocari Sweat for 1782 yen with 1500ml of deliciousness. Or you can go the powder route and get a box of aquarius powder for 2560 yen (currently on sale) which is 48g x 25 packs. One pack typically does 1 liter of sweet sweet goodness.

When in doubt, AIRCON!

Lastly, the best way to beat the heat in Japan, just stay indoors and turn on your aircon! I tend to turn my aircon on at about 25 degree and I’ll leave it on all day. Recently the local news have said it’s actually cheaper to run it constantly than to turn it off and on, but the choice is yours. Either way, be prepared to pay more for electricity in the hot summer months, especially if you live in Kumagaya!

Photo Credits:

Top Image: creampastaさん on PhotoAC

All other content (text) created by the original author and © 2022 MUSUBI by Borderlink

There is a Japanese saying, 日光を見ずして結構と言うなかれ or “Never say kekkō until you’ve seen Nikkō” (kekkō meaning beautiful, magnificent or “I am satisfied”) and there is no better way to sum up the of the beauty of the city of Nikko.

Where & What Is Nikko?

Nikko is a city located in the north-western part of Tochigi Prefecture, around 140 km north of Tokyo. Nikko is a famous tourist destination, attracting visitors from not only from other parts of Japan but also from overseas. The average annual temperature is about 12 degrees Celsius in the city, and about 7 degrees Celsius up in the mountains.

The colder climate helps to produce the beautiful landscapes in Nikko, as foliage suited for temperate and cold weather flourishes here. The mountains west of the main city are part of Nikko National Park and contain some of the country’s most spectacular waterfalls and scenic trails. Areas such as Kegon Waterfall and the marshlands around Oze Pond are must-see for any visitors.

Historically, Nikko is also known for being the resting place of shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu as as well as his grandson Iemitsu. Today Nikko is famous as a popular sightseeing point, but originally it was the center of religious devotion in the Kanto Region. Nikko was located on north of Edo. In Japan, north can be is considered a taboo (never sleep with your head pointed north, for instance). Ieyasu wanted to place himself in this very direction to protect Japan from the evil.

Where Treasures Abound

Tosho-gu it is considered one of the most beautiful and lavish shrines in Japan. It has been designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The structure is very famous for the ornate carving that splendidly decorates the entire buildings both inside and outside and from one end to the other.

In particular, the imposing Youmeimon tower gateway is famous for its lavish decorations that include over 300 dazzling carvings of mythical beasts such as dragons, giraffes, lions, and the Chinese sages. One interesting relief is the carving of elephants, because it was sculpted by as an artist who had never seen a real elephant.

The most well-known carvings are of the three monkeys hiding their ears, eyes, and mouth respectively. It represents the Buddhist doctrine of “see no evil, speak no evil, hear no evil” monkeys, which can be seen on the Sacred Stable.

There is a great deal more to explore throughout Nikko, so be sure to give yourself plenty of time when you do go check it out. And before you do, please check out another of our past articles about it!

Image Credits:

Cover Image: 上州太郎さん on PhotoAC

1 – ソライロさん on PhotoAC

2 – しょーた1002さん on PhotoAC

3 – しろももさん on PhotoAC

All other content provided by the MUSUBI Staff

Welcome to Part 2 of our explanation of the Japanese pension system! Previously, I introduced you to the basics. This week, I’ll explain a little more about the paths you can take with it depending on your length of stay in Japan and your financial situation. You can pay into it and collect upon retirement. You can also apply for a partial or full exemption. You can also meet halfway and pay into the system short-term, then collect a lump-sum payout when leaving Japan.

Pay In Now, Cash In Later

As I spoke about last time, paying into the pension system is highly advantageous if you plan on staying in Japan long-term. Not only is it legally required (unless you are able to get an exemption, see below) it’s also by far the easiest approach. It’s the one basically all residents of Japan are doing anyway, so everything is in place for it to be a fairly smooth process.

The downside is that you can only collect after age 65, or 60 at the earliest (though it’s preferable to wait, as there is a reduction in the amount you collet prior to 65.) Additionally, it’s important to know exactly which kind of pension you pay into, as the payout amounts differ between the employee pension plan, or kosei nenkin (厚生年金) and the national pension, or kokumin nenkin (国民年金). Either way, if you get that little blue or orange book in the mail, be sure to hang onto it, as well as any other pension-related numbers.

For more information about collecting pension, here’s a simple guide on GaijinPot.

Getting a Pension Exemption

If you have difficulties in making payments, you can apply for an exemption program called hokenryo menjo seido (国民年金保険料の免除制度). In addition to full exemption and the partial exemption, the program is also available for those who are younger than 30 years of age and want to delay the payment without penalty jakunensha nofu yuyo seido (若年者納付猶予制度).

Application forms are available at local pension offices and the national pension section at local municipal offices, but make sure you have what you need before going. This will be your koyou hoken hikokensha bango (雇用保険被保険者番号) or employment insurance record number. Once you have that, head to your city hall and apply for the exemption. It will take some time and paperwork, but within 2 months you should get a letter in the mail.

While this method is legal, its success rate will depend on your situation. If for whatever reason your pension exemption application is not accepted, alternatively you will most likely be put onto a reduced payment plan, in which the monthly fee you pay is significantly less than what it would be had you not applied for an exemption. Once you get your result, be sure to confirm if it is a full or partial exemption. For more information, please see the government’s (English-language) guide.

Obtaining the Lump-Sum Payout

If you have been paying into the pension system but are planning on leaving Japan before retirement age, it is possible to withdraw the last three years’ worth of your contributions to the pension as a lump sum and have it paid into a foreign bank account. This method is especially recommended for those planning to work as ALTs for at least 3 years before returning home.

To claim the lump sum payout, you will again need to fill out all the necessary paperwork. This process can be started in Japan or done overseas, but make sure to do it within 2 years of leaving Japan. For more information, please see the Pension Service’s guide.

Conclusion

Although the Japan Pension System can seem like a burden to many of us living in Japan, there are different approaches we can take to managing it. If you’re looking at living in Japan long-term (and especially applying for permanent residency or citizenship) it’s worth biting the bullet now and paying in. You will be able to collect later, and in addition to other personal savings or sources of income, it can be a great way to make your twilight years a little more comfortable. I wouldn’t recommend relying solely on it, but as a supplement to other money, it’s effective.

For short-term stayers, we do have the right to opt out of it, or collect on 3 years’ worth if we did pay into it. Making those choices require a few extra trips and documents, but they can be done and done legally. Above all, I believe it is highly worth it to stay on the right side of the law and always do things by the book. Ganbatte!

Images:

Cover Image: FRANK211さん on PhotoAC

1: 白つばきさん on PhotoAC

2: mirai0002さんon PhotoAC

4: Hadesさん on PhotoAC

All other images & content provided by the original author.

Hokkaido, Japan’s very own ‘Last Frontier’, is a place with much to discover. You have to do a bit of searching sometimes, but it’s there between the frosty mountains and snowy fields. Here are six of our favorite spots and features of Japan’s most northern prefecture.

Sapporo Snow Festival

The Snow Festival is held annually in Sapporo over seven days in February. Sapporo’s signature festival began as a one-day event in 1950, when six local high school students built snow statues in Odori Park. Now, the festival attracts millions of visitors a year. An International Snow Sculpture Contest has been held at the Odori Park site since 1974.

Sapporo Concert Hall

The concert hall, “Kitara”, is a municipal musical venue located in Nakajima Park, Sapporo. Established in 1997, the building is owned by Sapporo City, and was opened on July 4, 1997. The concert hall is home to the Sapporo Symphony Orchestra, and its regular concert is held in the hall each year.

Hakodate

Hakodate is a city and port located in the Oshima Subprefecture of Hokkaido. The city was Japan’s first city whose port opened to foreign trade in 1854. As a result of the Convention of Kanagawa, it used to be the most important port in northern Japan. Boasting a population of 264,845, this peninsular city is home to the Hakodate Fish Market and Goryokaku Park.

Kyowa Marshes

The mountains north of Kyowa-cho, Hokkaido boast beautiful natural marshes which are wonderful for viewing during the non-winter months. They’re also a popular place for stargazing, due to their elevation and the lack of light pollution.

Doushinkan Folk Toy Museum

This charming little museum is located in the small village of Kamoenai, Hokkaido. In September 1998, the former Sannai Elementary and Junior High Schools were renovated. Old toys and kites from all over Japan were gathered to be displayed here. Some of these treasures have been passed down since the Edo period. This is a place full of wonder and nostalgia, and truly worth a visit.

Ganso (Original) Ramen Alley

The Ganso Sapporo Ramen Yokocho is a tourism hot spot in Susukino featuring 17 popular miso ramen shops. The 42-meter long narrow alley is always crowded with visitors from morning until night. It is also popular among locals as their last stop of the night for a ramen snack after spending an evening out drinking in Susukino. The alleyway offers up many different flavors of miso ramen, from a simple traditional take on the Sapporo staple to ones with particular choices of ingredients.

And that’s just scratching the surface. There’s plenty more to find here and in every other prefecture across Japan. Which one’s your favorite?

Image Credits:

Cover Image: meguraw645 on Pixabay

All other images were provided by the original author and are Ⓒ MUSUBI by Borderlink

School lunch is one of the most unique parts of working at an elementary or junior high school in Japan. Coming from America, where we had a relatively set menu (Pizza Thursdays, Hamburger Mondays, etc.) it can be downright shocking. So much variety! So many unfamiliar foods! So much milk!

While there will be much repetition throughout the school year (even throughout the month) it is possible to never eat the exact same combination of items even after years of teaching at various schools. Sometimes it’s curry, but with salad on the side. Or maybe it’s curry, but with quail eggs. And there can even be curry, but one of the other items of the day is フルーツポンチ (“Fruit Punch”, or mixed fruits). The possibilities are seemingly endless.

Here is a typical week of school lunches at an anonymous school in Saitama prefecture. At this particular school, school lunch is served in metal trays, but this might not always be the case at your school. Separate plastic dishes or trays seems to be more common these days. While some schools provide chopsticks and spoons, others require students (and teachers) to bring their own (that’s what the green thing off to the side in some photos is).

Finally, though this was a bread-heavy week, it’s just as common to go a week with 4 out of the 5 days having rice, or having noodles on some days. You just never know what you’re going to get (unless you can read the schedule, of course). Here’s what we had:

Monday

Borscht or Minestrone seem to be one of the more polarizing items on the school lunch menus, but they make a great complement to bread. In this case, twisty bread!

Tuesday

We mentioned quail eggs before, and we weren’t kidding. They turn up in soup quite often. Also, while on this day the rice is of the standard white & sticky kind, there are many others such as barley rice, pickled plum rice, and others.

Wednesday

Creamy stews and even clam chowder show up from time to time. The bread of the day can sometimes be hamburger-style buns, which you might put another item into (such as korokke).

Thursday

As you’ve seen from previous days, lunch generally consists of a base starch item (rice, noodles, bread) a soup/stew, a vegetable or tofu-based dish, and a meat item. For the latter, today had mini-nikuman (Siopao).

Friday

We finish off the week with pumpkin soup, bread, fried fish and corn salad. Also note the presence of “drinkable yogurt”. Dessert-type items pop up occasionally, from fresh fruit to chocolate pudding.

As mentioned, that’s just one week! There are plenty of other school lunch combinations to experience- what’s your favorite?

Want to try Japanese school lunches for yourself? The best way to do so is to become an Assistant Language Teacher, or ALT. Find out more about how you can become an Assistant Language Teacher with Borderlink today!

Images:

All images used in this article were provided by the original author and are Ⓒ MUSUBI by Borderlink

Top Photo: gonzo5500さん on PhotoAC

Japan is a nice, peaceful and safe country to go cycling. Bicycles are widely used in Japan for going to school, work or doing errands. There are various types of bicycles, from the the mama chari or “Mom`s Bicycle” to various off-road models. For a more comprehensive guide, see our previous article about cycling in Japan!

Renting a Bike

If you wish to explore Japan through cycling, there are rental bicycles available for the tourists. The rental fees are roughly from ¥100-300 per hour, ¥400-800 half-day or ¥1000-1200 whole day. Our advice is to go with a daily rental; it’s the best deal if you’re planning on cycling longer distances, and won’t cost as much if you go over the half-day mark. If you plan on biking in Tokyo, here are a few rental suggestions.

Handy Tips To Keep In Mind

You have to keep in mind the following rules when you go cycling in Japan:

1. Cycling under the influence of alcohol is strictly prohibited. Don’t do it!

2. Use helmet and other protective gear. You may see people riding without these, but it is becoming more and more discouraged (and the potential injuries that can result are not worth the risk. Drive and bike safely!)

3. Avoid using electronic gadgets such as smart phone while cycling. Better to stop in a safe place if you need to use your gadget.

4. Be conscious of the traffic and street signs. Also be careful of pedestrians- in any collision, legally speaking, the cyclist is at fault.

5. Park your bicycle at designated parking areas. Ticketing is very common in big cities, so be smart and find proper parking.

6. Side-by-side cycling and two adults on one bike are strictly prohibited.

7. Bicycles are not allowed in trains.

8. Your bicycle must have working headlights and rear lights.

9. Register your bicycle at the local police station for safety and protection from thieves. While Japan is still a relatively safe country, theft of unattended or unlocked bicycles is a possibility. Register and get a lock!

Japan is a beautiful and relaxing country to explore. The landscape is refined, and in general it has great cycling infrastructure, even in cities. Japan is a must-see destination to all bike travelers. let’s enjoy cycling!

Photo Credits:

Top Photo: gonzo5500さん on PhotoAC

Additional photos provided by the original author, used with permission

All other content (text) created by the original author and © 2022 MUSUBI by Borderlink

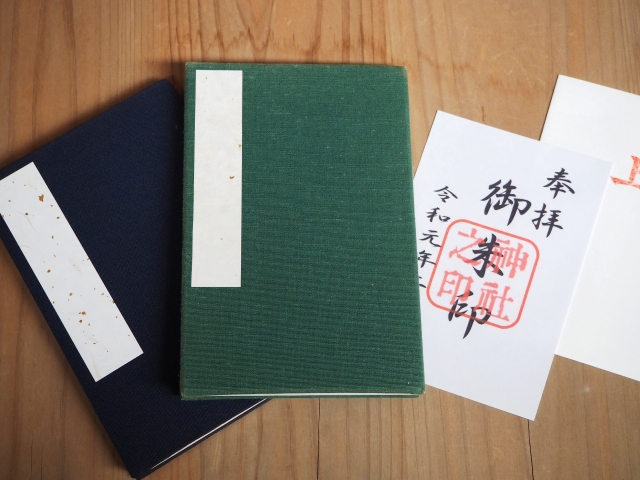

Many of us have had a chance to visit either a local shrine or a temple in the course of our stay in Japan; being the far-most iconic locations that define Japanese-ness that a foreigner may visit. Usually located close to where we live, most of us realize that these places of devotion has turned into a sort of a cultural center, offering local experiences that is part of many Japanese` world-view.

What is not widely known, however, is the presence of goshuin (御朱印) – sort of a religious proof that one has made the pilgrimage to that particular shrine or temple. Usually masterfully hand-written, these goshuin has seen a resurgence of its popularity in the recent years, as many people even make long trips just to collect them. It is one of the least-known Japanese cultural practices, and it offers an insight into the Japanese mind and soul like none other.

The History of Goshuin

The history of goshuin dates from the middle ages, when temples offered them as a certificate whenever a religious devotee dedicated a Buddhist sutra as a sign of their faith. This became a popular hobby in the Edo period, when traveling became somewhat easier and people began to collect them as mementos of their journeys.

In recent years, collecting goshuin has once again become a popular hobby, with many Japanese, both young and old, participating in such pilgrimages in order to collect them.

What is a Goshuin?

What, then, exactly is a goshuin? It is a combination of seals and writings that a temple or a shrine may offer in exchange for a small fee. Usually ranging from 300 to 500 yen, some of these goshuin are extremely artistic and highly-sought after by some of the collectors.

Although the COVID-19 pandemic has forced many shrines and temples to offer a pre-written goshuin, many of them are directly written and stamped on a pre-arranged booklet called the goshuin-cho, which are usually sold between 800-2000 yen at whenever stationaries are sold. Many of the shrines even have their own goshuin-cho. These are often elaborately decorated in traditional Japanese craftsmanship.

Where to find Goshuin

One of the closest shrines to offer such a goshuin in Omiya is the Hikawa Shine. Considered by many to be the local guardian shrine, Hikawa Shrine`s goshuin is quite simple: It lists the day of the visit and the name of the shine, centrally stamped with the shrine`s seal. Its simplicity, however, is masterfully covered by a beautiful calligraphy that many foreigners would surely find the essence of Japan.

Goshuin, though having its origins in acts of religious devotion, has become an easy way to collect memorabilia that traces your steps in domestic travel. Many goshuin-cho`s allow for up to 40 or so goshuin`s to be collected, making it a perfect way to have a memorabilia of your prolonged stay in Japan.

Furthermore, these carefully written works of art are sure to become the center piece of your goods from Japan. In the end, goshuin is an easy way to have a fun, personal experience with a more esoteric side of Japanese culture.

Image Credits:

Cover & other goshuin images (1) (2): hakusyuさんon PhotoAC

(3) Hikawa Shrine image: しろももさん on PhotoAC

All other content provided by the original author.

While life in Japan can be one full of adventure and excitement, there are also many responsibilities that newcomers may not be aware of. One such obligation is the need to pay into the national pension system. It isn’t always explained very well in advance, which can lead to problems down the road. It just seems to be something you need to figure out for yourself. But no more! Here is a basic beginner’s guide to the ins and outs of the pension system.

Help! I’ve got mail

For those new to Japan, at some point after registering your address, you’ll get a mysterious thick envelope full of slips. You get a lot of junk mail though, so maybe you ignore it, or toss it into a pile to be forgotten about.

Then you start getting letters. These seem non-threatening and reasonable, but still, nobody’s really explained what they are or what you do with them. Maybe your Japanese reading skills aren’t quite there yet, so you ignore them too. Eventually the same letters come in with red text and lots of exclamation marks.

Then you start getting letters. These seem non-threatening and reasonable, but still, nobody’s really explained what they are or what you do with them. Maybe your Japanese reading skills aren’t quite there yet, so you ignore them too. Eventually the same letters come in with red text and lots of exclamation marks.

We ask our expat friends for advice. But they keep telling us that nobody has to pay for pension. It’s like paying for NHK- there’s all sorts of loopholes and even a sizable portion of Japanese people don’t actually do it. Yet we can’t help but feel that something is off.

A confusing necessity

On the one hand, Japan’s taxes and expenses take away a large chunk of our income as it is, making the monthly Japan Pension bill fee like a straw which can break the camel’s back. We’re already paying for housing, plus everything else. On the other, not paying pension feels like not paying taxes. There’s just something wrong about leaving it hanging over you like that.

Then you start to worry. What if some suits shows up to your door one day demanding a cartoon sack full of money you don’t have? What if it leads to further trouble down the line, such as when it comes time to renew your visa or purchase property if you’ve decided to stay long term?

When one takes a step back, paying seems obvious, right? If you live in the US for example, you pay into Social Security; the same would be true of anywhere else with a similar system. Yet for some reason Japan’s version has always had a labyrinthine air about it for overseas residents.

Fortunately, there are ways to navigate and understand the pension system so that you can benefit from it too. If your plan is to stay long term and make monthly payments, you can reap the rewards. If your future likes elsewhere, it is legally possible to apply for an exemption (more on this later).

What is the National Pension System?

Kokumin nenkin (国民年金) or National Pension, is a system for all residents between the ages of 20 and 59 years old, including foreign residents living in Japan. By paying monthly premiums for over 10 years, an individual will be able to receive a pension payment back to assist them in retirement (over 65). While it is generally recommended to have other sources of funds (such as personal savings) the pension exists to make retirement easier (even then, some in Japan choose to continue working part-time jobs even after 65!)

Do I have to pay into the National Pension System?

The straight answer: yes. All residents, irrespective of their nationality, must be covered by the National Pension system and pay contributions by law. Following the introduction of the My Number (マイナンバー) system, the Japanese government has been a little more strict in ensuring all eligible residents who can pay are paying in.

It’s important to note that there is something called the employees’ pension insurance (kosei nenkin, 厚生年金), part of the social insurance (shakai hoken, 社会保険), system which combines it with health insurance (kenkou hoken, 健康保険).

It’s important to note that there is something called the employees’ pension insurance (kosei nenkin, 厚生年金), part of the social insurance (shakai hoken, 社会保険), system which combines it with health insurance (kenkou hoken, 健康保険).

If your employer enrolls you in social insurance, they should pay part of the monthly premium. You should not be paying into the National Pension separately, as it’s essentially part of the same system. And you don’t need to be paying in twice!

Why pay into the Pension System?

A misconception among some foreign residents living in Japan is that they don’t have to pay. If you’re only planning to live here for a few years, and not a citizen, why bother, right? The problem is that you’re running into a potential legal minefield if you do. Paying into the pension system is a requirement of all residents of Japan- including citizens and non-citizens alike. This is because non-citizens are able to benefit from the pension system as well. There are advantageous to paying in even if you only plan on staying less than 5 years.

For example, many come to Japan to teach English for 2-3 years and then decide to move on to another country or return home. What they don’t often realize is that they can receive a portion of their pension payment back.

For example, many come to Japan to teach English for 2-3 years and then decide to move on to another country or return home. What they don’t often realize is that they can receive a portion of their pension payment back.

If one decides to leave Japan permanently before retirement age, and meets the conditions (and has paid in for at least six months), they can collect the money owed to them as a lump-sum amount. For short-term stays, this gives one a little extra cash upon leaving, which can help with settling down for the next chapter of your life.

For those looking to stay long-term, it’s pretty much a no-brainer. If your plan is to live and work in Japan until retirement age, you’re going to want to make use of all the benefits afforded to you. Much like its healthcare, the Japanese pension system is excellent for those who learn about it, understand it and make use of it.

Okay, but do I need to pay?

As mentioned, there is a completely legitimate and legal way to get an exemption from the pension system. We’ll cover that in Part 2 of this guide, coming soon!

Until then, enjoy Golden Week!

Images:

Cover Image: きぬさらさん on PhotoAC

1: KK2890さん on PhotoAC

2: ゆきだるまさん on PhotoAC

3: sommeilさん on PhotoAC

All other content provided by the original author.